Identification of the woods used in the construction of the coffins was undertaken by the examination of samples by scanning electron microscopy (Cartwright, 2018).

It is important to note that some of the smaller pieces of wood and many of the connectors (dowels and tenons) were not accessible for sampling, so the description here of the carpenters’ materials is not comprehensive. However, all the principal elements of each part of the coffin set were identified by examination of the 152 samples taken. The woods used were the native sycomore fig (Ficus sycomorus), sidr (Ziziphus spina-christi), Nile acacia (Acacia nilotica), tamarisk (Tamarix aphylla) and the imported cedar of Lebanon (Cedrus libani).

| Coffin part | Structural elements | Connectors |

|---|---|---|

| Mummy board | Sycomore fig | Not accessible for sampling |

| Inner coffin lid | Sidr, sycomore fig, tamarisk | Sycomore fig, sidr, acacia |

| Inner coffin box | Sidr, sycomore fig | Sycomore fig |

| Outer coffin lid | Sycomore fig, tamarisk, cedar of Lebanon | Sycomore fig, cedar of Lebanon, acacia |

| Outer coffin box | Sycomore fig, tamarisk | Sycomore fig, sidr, acacia |

Table 1: Summary of woods used in the construction of the coffin set

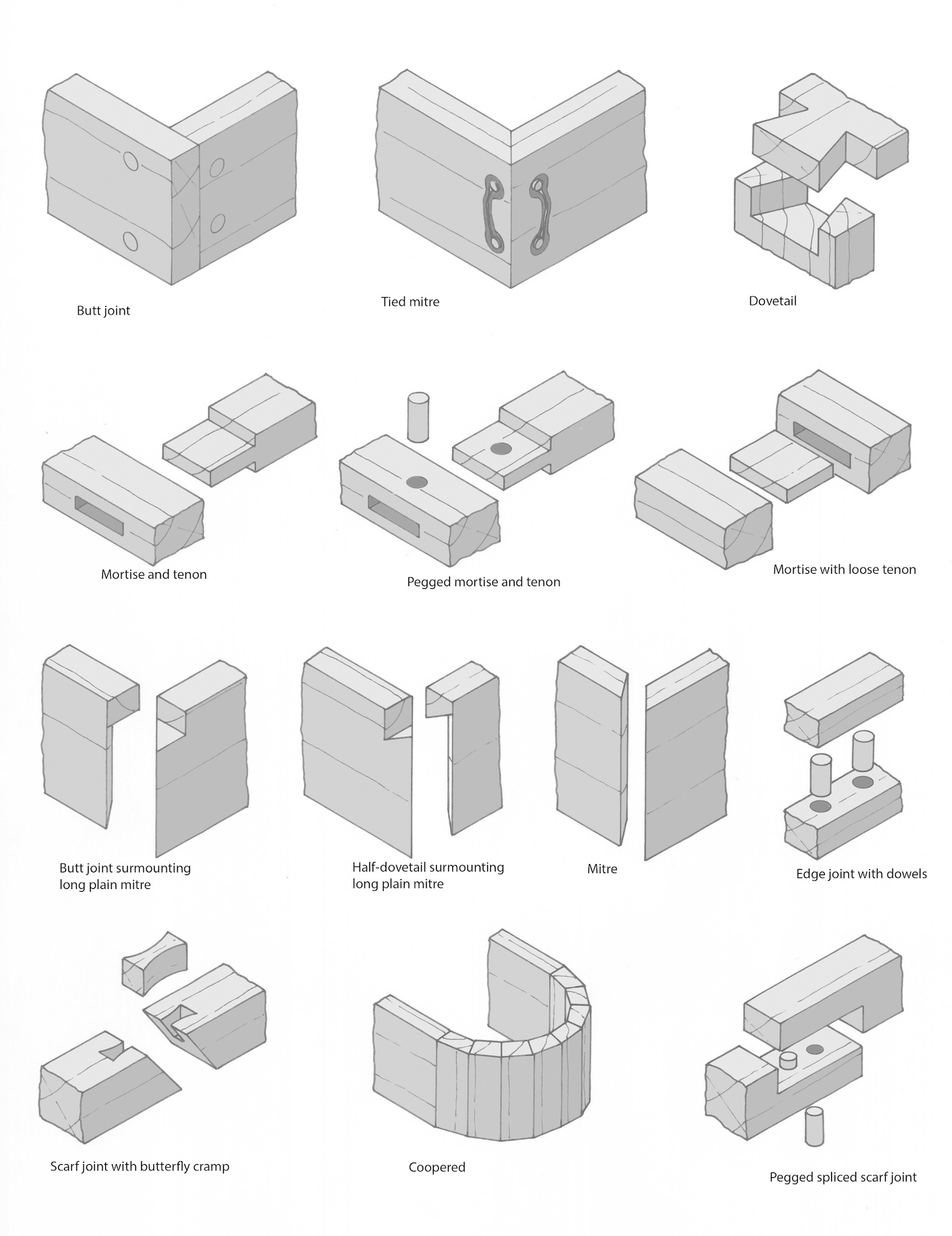

The following joints were used to put the coffins of this set together:

The construction of the mummy board and the outer coffin were determined by direct observation and X-radiography.

The mummy board is constructed from two long, almost flat planks, held together with loose tenon joints. The face and hands are dowelled on. The foot section is lost, but there are dowel holes and the remains of original filler paste along the broken bottom edge of the board. On the back of the board, a bare wood surface with animal glue, eight small dowel holes and a ridge of coarse filler paste along the inner edge are all that remain of a rim around the head.

The main structural elements (single foundation board and rims) of the outer coffin lid are of sycomore fig. Each rim has a short section of a separate board, added to the foot end with a scarf joint. The dowelled-on face and the right hand are also sycomore fig, but the five-piece footboard and the left hand are made of tamarisk. Two patches added to the proper left side of the wig are one of cedar, one of tamarisk. In the eight rim mortises, three of the loose tenons used for closing the box and lid together survive. Two are cedar and one is sycomore fig.

Each long side of the outer coffin box is made of two shaped planks, the proper left lower plank brought to its full length by a short section of wood attached with a scarf joint. The foot end (also made of two planks) is held to the sides with pinned dovetail joints. The head end is roughly hewn from a single massive piece of sycomore fig and the exterior surfaces of the side planks from the shoulders upwards are built up with a combination of dowelled-on wood patches and paste to match the thickness of the head end wall. The base boards of the box are mirror images of each other, suggesting that they come from a single length of wood sawn along its length then opened out and laid side by side. A tamarisk insert sits between the two boards that make up the base of the box and is the only structural element that is not made from sycomore fig. Apart from the dovetail and scarf joints mentioned, the construction of both box and lid is dowelled.

The construction of the inner coffin was determined by direct observation, X-radiography and CT scanning.

In contrast to the mummy board and the outer coffin, the inner coffin presents a rather more complex mixture of woods and construction methods. The foundation board of the lid is one large plank of sidr with rim pieces of sidr and sycomore fig attached by angled dowels. Sidr is a dense, hard and rather knotty wood and the CT images show clearly a massive fault at the centre of the board. The carpenters experienced some difficulties with this: the plank appears to have split along its length, possibly when a dowel hole was drilled or the dowel subsequently inserted to make one of the fixing points for attachment of the face. The two halves were then pinned together with a shallow butterfly cramp in the chest. The central section of the plank below this had to be chopped out (possibly it was damaged) and replaced with wooden fill pieces. The surviving (proper right) hand is sidr, the coffin face is sycomore fig. The feet and the footboard (which is attached to the rims by pegged dovetails) are made up principally from one piece of sycomore fig, but with several fills, wedges and additions. Most of these are sycomore fig but they include also sidr and tamarisk. Apart from the butterfly cramp, two pegged tenons in the footboard and the two dovetails, the construction of the lid is dowelled. The seven surviving rim tenons are made of sidr, acacia and sycomore fig.

The base boards of the inner coffin box consist of two long planks with additional fill pieces all held together with loose tenons. These tenons were drilled to be pegged, but the CT scan image shows that the peg holes are empty. Each long side of the inner coffin box is constructed from two shaped planks of sycomore fig, joined edge to edge with massive pegged tenons. The exterior surfaces of the sides above the shoulders are patched with dowelled-on pieces of wood. The head end of the box is a coopered construction in which three pieces of wood (two sycomore fig and one sidr) each cut with very slightly angled edges, have been put side by side and joined with loose tenons to form a curve. The sides of the box are fixed to the foot end boards with dovetail joints, reinforced with dowels, and to the base boards with angled dowels.

To minimise the effect of warping on the overall structure, the carpenters of the coffin box ensured that the heartwood was a different way up on each adjacent plank, as shown in a single CT image (transverse) through the box.

Cooney has identified a range of different types of re-use on 21st Dynasty coffins from the simple inscription of a new name, through partial redecoration to complete coverage with a new decorative scheme or scrubbing off the original layers and replacing them. The most comprehensive refashioning and, often, the hardest to detect is when coffins have been broken down structurally and the wood incorporated into new coffins (Cooney 2017). The coffins of Nespawershefyt fall into this last category. Apart from modifications to Nespawershefyt’s titles (Strudwick 2017), there is no evidence of over-painting or new decorative layers, only a few enigmatic surface details to suggest that the intact and highly accomplished finish may be masking some unusual fills and construction features.

N.B. There are 19th and 20th century repairs on all three elements of the set were used primarily to reinforce weak elements and joints. They consist of:

Mummy board A metal bar screwed across the width of the mummy board, to secure the structure above the break at the feet; and two small nails at the shoulder (all now removed).

Inner coffin lid One screw and one nail in the rim pieces at the head end; a single screw and a metal plate screwed into the foot section of the inner coffin lid; and two short modern wooden dowels, substituting for broken-off ancient dowels, which attached the footboard to the central plank of the foundation board.

Outer coffin box Numerous handmade iron nails holding the base boards to the side panels and the side panels to each other; three large, modern oak dowels (in ancient dowel holes) holding the proper right side panels to the head end. All the evidence discussed below is found under original paste and varnish layers and would appear to show ancient re-use of wood.

The only feature of the mummy board that may indicate refashioned or re-used wood is a redundant dowel hole, filled with a dense material (presumably paste) and revealed as a pale, opaque feature on the X-radiograph along the internal join of the two long planks.

Most of the features described below are also shown in this animation.

A fairly simple example of re-use is illustrated by the stack of CT images through the depth of the footboard. Two horizontal planks are held together with dowels to create the footboard. However, also within the depth of the top plank, immediately behind the proper right side dowel, there are remains of half a redundant mortise, with a pegged tenon still in place, but sliced across. Clearly this is re-used wood from a wider plank that has been cut down.

The current rim mortises of the box (marked by blue arrows in the image) are all about 40 to 50mm in length. These line up with the rim mortises on the lid. But, covered with a paste and varnish layer and scarcely visible to the naked eye, there is a second set (marked with red arrows), each about 60 to 70mm long and each filled or part-filled with a piece of wood that is wedged into the gap and covered over with paste. The CT images of the rim (6c) and of a section of the side wall of the coffin box (6b), help clarify the features and also show that these fill pieces are not old tenons. The grain in a tenon is always perpendicular to the grain of the piece of wood in which it is sitting in order to give strength to the joint. The grain in all of these pieces runs in the same direction as the grain in the side panel. They are just fill pieces.

The top plank on each side of the box is a single piece of wood from the foot end up to the point where the side joins the coopered head of the coffin box. The shape of these planks coupled with the position and alignment of the four old mortises on each side strongly suggests that the panels are from another coffin. It is possible of course that the carpenter of Nespawershefyt’s coffin simply misplaced the rim mortises when he first cut them and had to reposition them. However, the inference that these panels have been adapted from an earlier coffin is further supported by the positioning of the new mortises. Examination of the addition and subtraction of pieces of wood to accommodate this and possibly to change the profile of the sides also confirms it.

If the mortises are numbered from the head down, the second and fourth on each side are in front of, but lined up with, the old mortises. The third new mortise on each side, sits significantly closer in towards the inner side of the panel. This position corresponds to the slight inward curve of the coffin’s outer profile to indicate the position of the knees between the swell of the thighs and the calves.

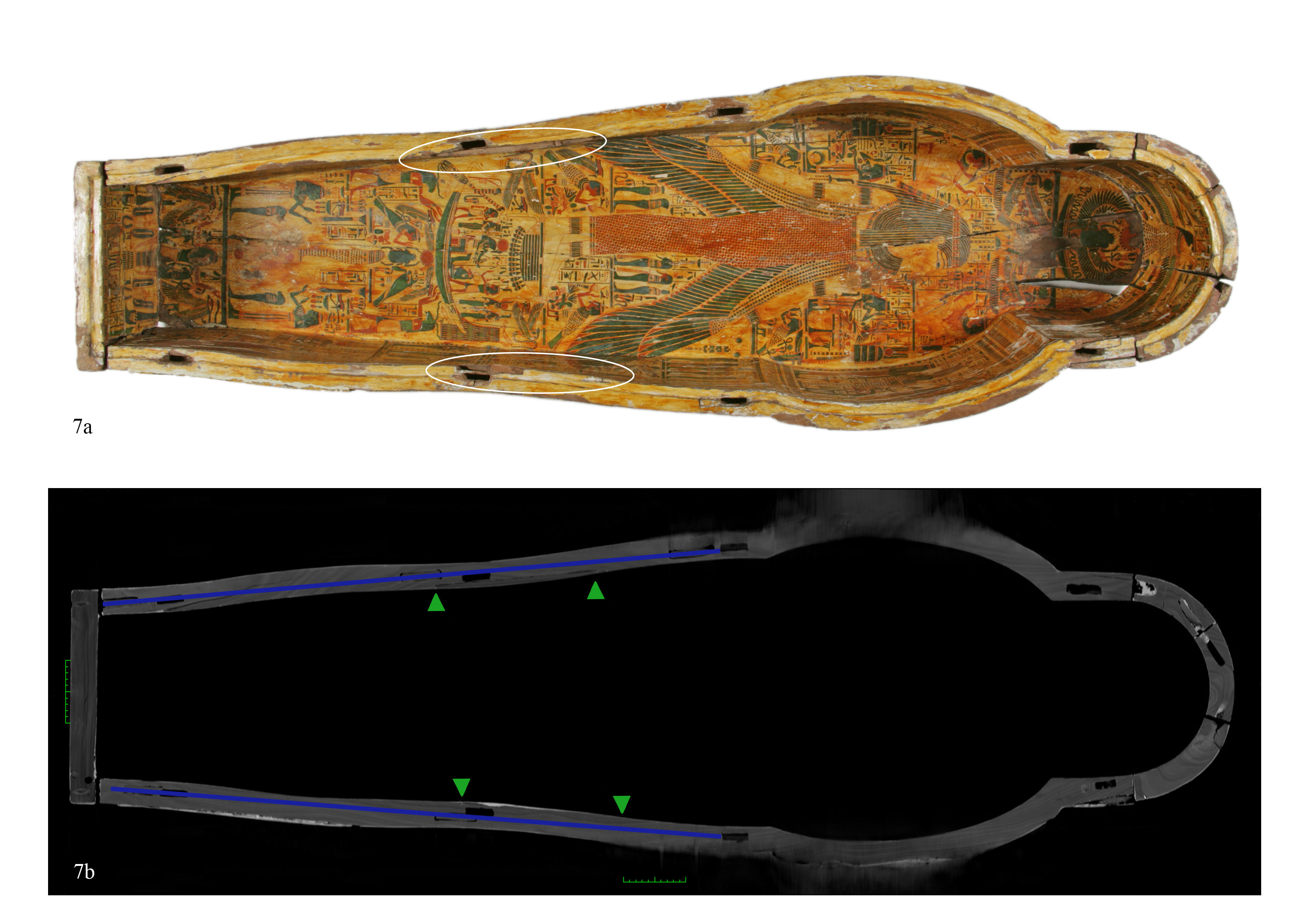

On the internal wall at this point on each side, a long sliver of wood has been cut out and replaced with a piece that is tapered at both ends but wider in the middle, thus creating a very gentle inward curve on the inner wall of the box (7a). The added pieces are dowelled into place. A line drawn through the old mortises shows that the outer wall of the earlier coffin may have been cut away to give a more curvaceous shape, defining the lower leg, knee and thigh (7b). On the inner side this has been replicated by letting in the new piece of wood to create the new profile and also to maintain the relationship of the new mortises to the centre of the wall.

Where the side planks join the coopered head, the opposite mechanism appears to have been used. Here the current rim mortise is positioned further towards the external surface of the panel, so there is a cutting back of the interior wall and adding to the exterior. This effect is seen most clearly on the proper left side of the box (6a and 6c and 8a and 8b). As wood has been cut away from the interior, the side of the old rim mortise has been sliced off. A fill piece has been inserted where the original tenon sat. On the exterior wall a piece of wood has been chopped out and a new piece let in. It is all held together with a small dowel and has been made good by filling in with paste.

There may have been some shaving down of the interior wall along the length of the coffin, but the effect as seen in the CT scan transverse images is slight and not entirely consistent. It is most obvious where the wall of an internal mortise and tenon joint, which holds the bottom and top planks together, has been penetrated and the holes in the wall that this has created have then been filled up with paste. This is the case in three of these eight internal mortise and tenon joints. It is slight and subtle and may be only a final thinning of the wall, but it may also indicate a reshaping of the wall from a straighter to a more outwardly flared profile.

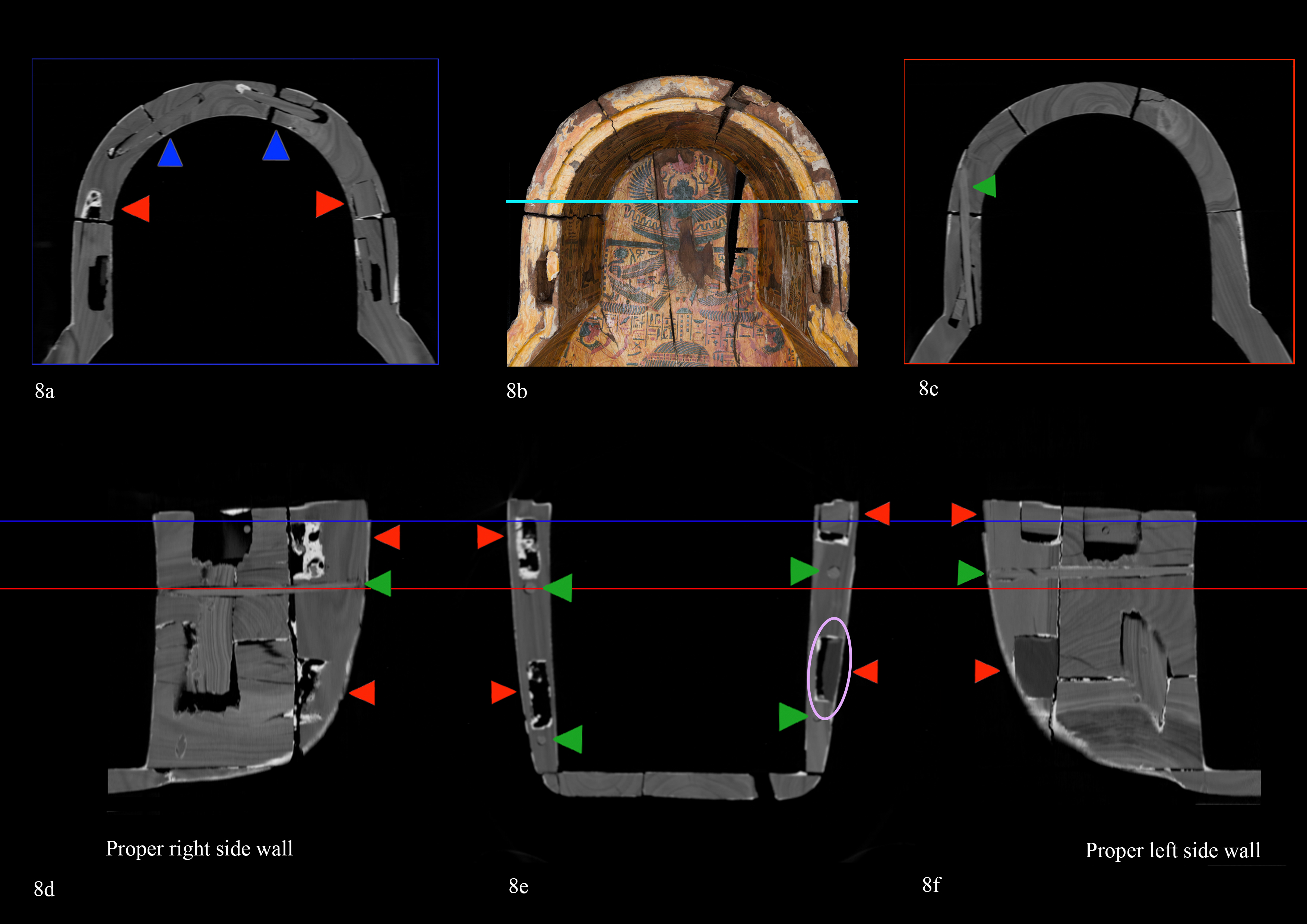

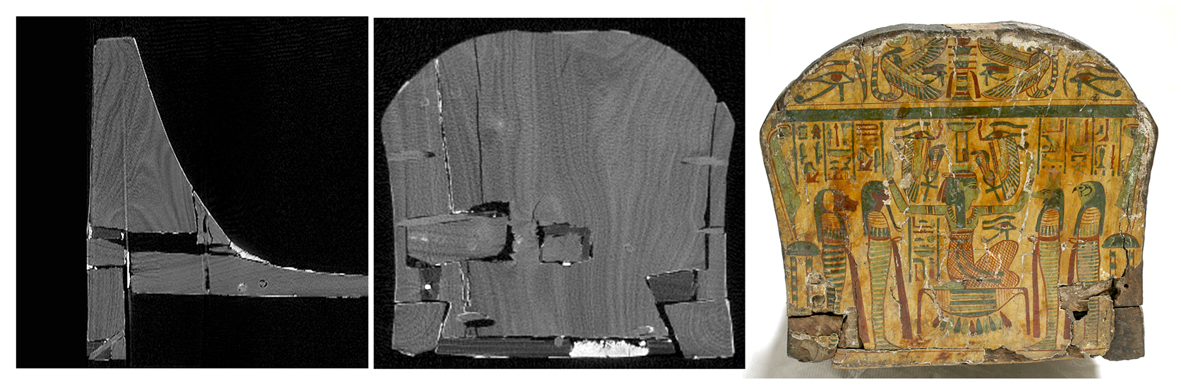

The coopered head of the box also shows signs of adaptation. The central panel has been attached to the outer panels with relatively well-fitting mortise and tenon joints (8a) on each side, marked by blue arrows on the image. There is one towards the top of the structure, the other towards the bottom. But where the outer coopered panels attach to the long side panels of the box there are remnants of much bigger mortise and tenon connectors (8a, 8d, 8e, 8f) that are now redundant and have been cut across. The head end is now attached to the sides with four very long dowels that cut right through all this earlier structure (8c and 8d-f, marked by green arrows).

These features of the coopered head end of the box and attachment of this to the side panels are shown here in a film of the three different views (transverse, coronal and sagittal) captured by the CT scanning.

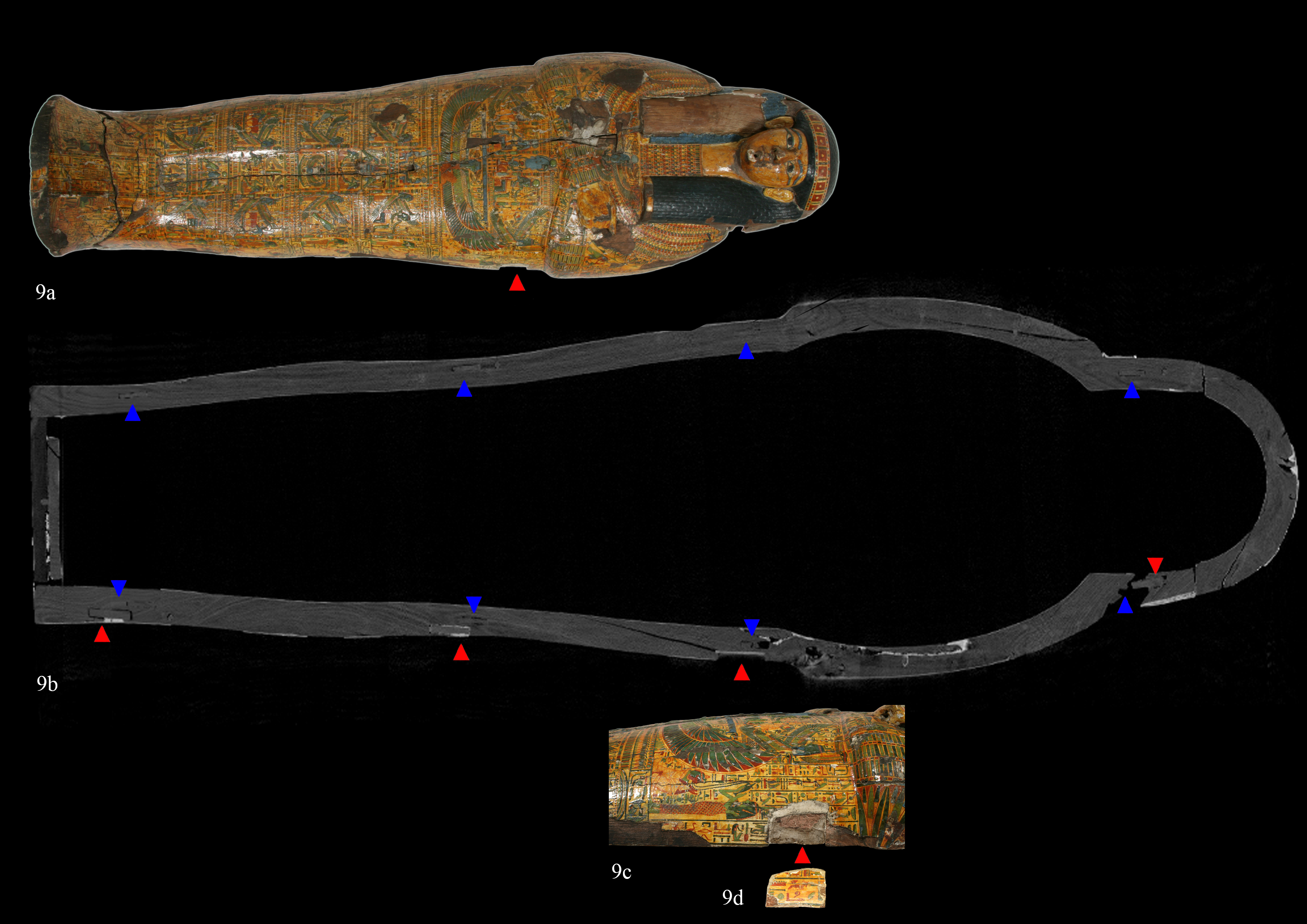

On either side of the lid the rim consists of a long piece of wood that is attached to the big foundation board. Marked with blue arrows on the CT image (9b) are the current rim mortises and in them (except for the proper left side head end mortise, which is empty) the tenons that make the current closure system of the lid to the box. But on the left hand side only, there are, as on the box, four longer mortises (marked by red arrows), that have been cut across, filled with pieces of wood and covered with paste. In reshaping the outer profile of the rim piece, the carpenter has cut rather severely into the second old mortise from the head end (9a and 9c). The resulting hole was then filled with a new piece of wood (9d), stuck in with glue and paste, and decorated over. This piece of wood has long been detached from the coffin and the relationship apparently not understood until recently. It has the accession number E.1.1867.

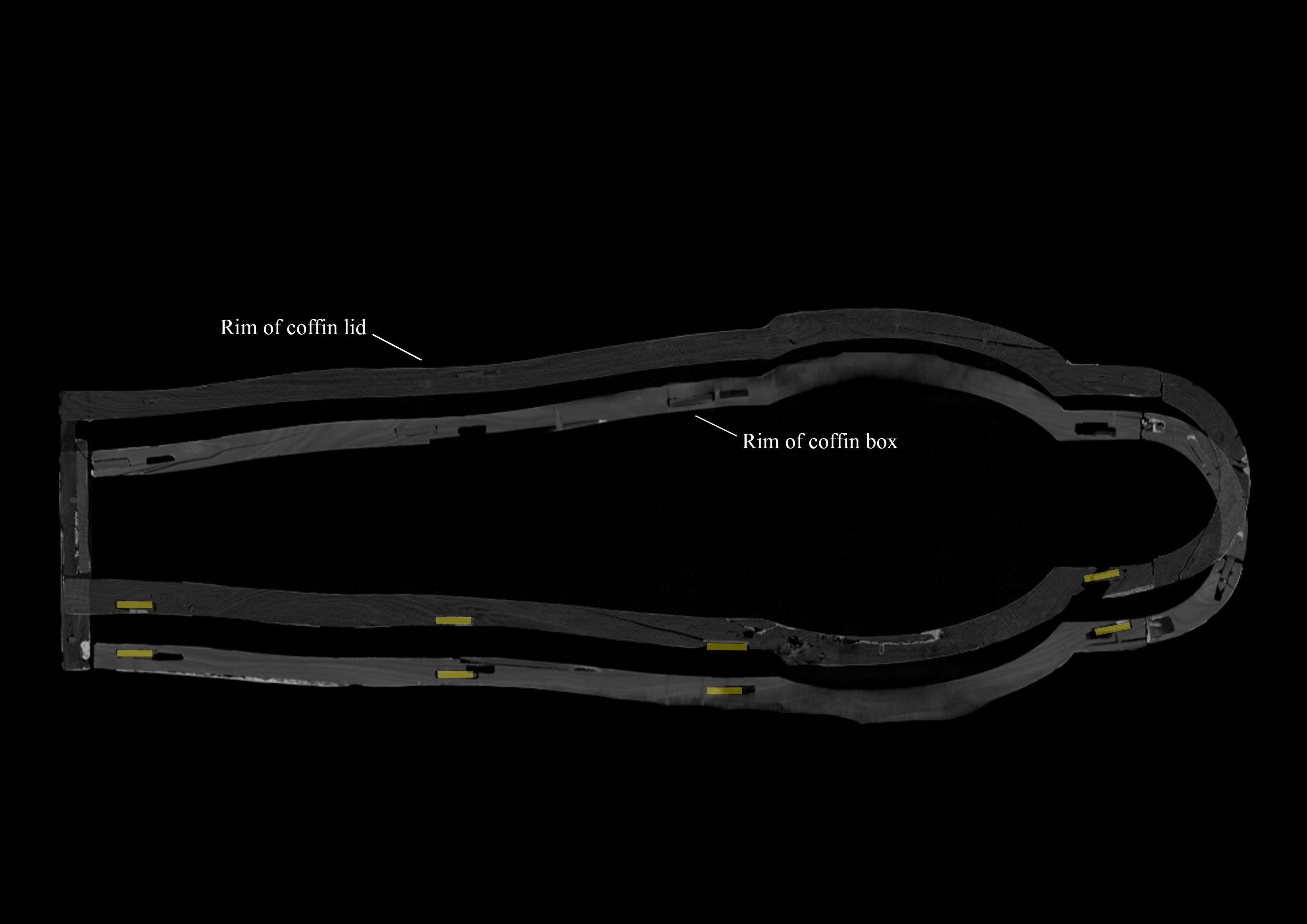

When the CT image of the lid rim is put onto that of the box rim it is notable that these old mortises line up remarkably well, possibly suggesting that this lid rim and the proper left side panels of the box may originally have been part of the same earlier coffin.

There are other more minor examples of re-used wood, for example, the central fill piece in the leg area of the foundation board has an old cut-through mortise that has been filled up with a fragment of wood and a mass of paste.

The construction of the footboard appears to be partially re-cut and is extensively patched, but the precise nature of the re-use is not yet clear. On the foundation board of the lid there are four redundant dowel holes (three filled with cut-off dowels) that penetrate only the depth of this board and that are not used at all in the current connection to the feet of the coffin. However, their position and regular spacing suggest that this may have been their original function.

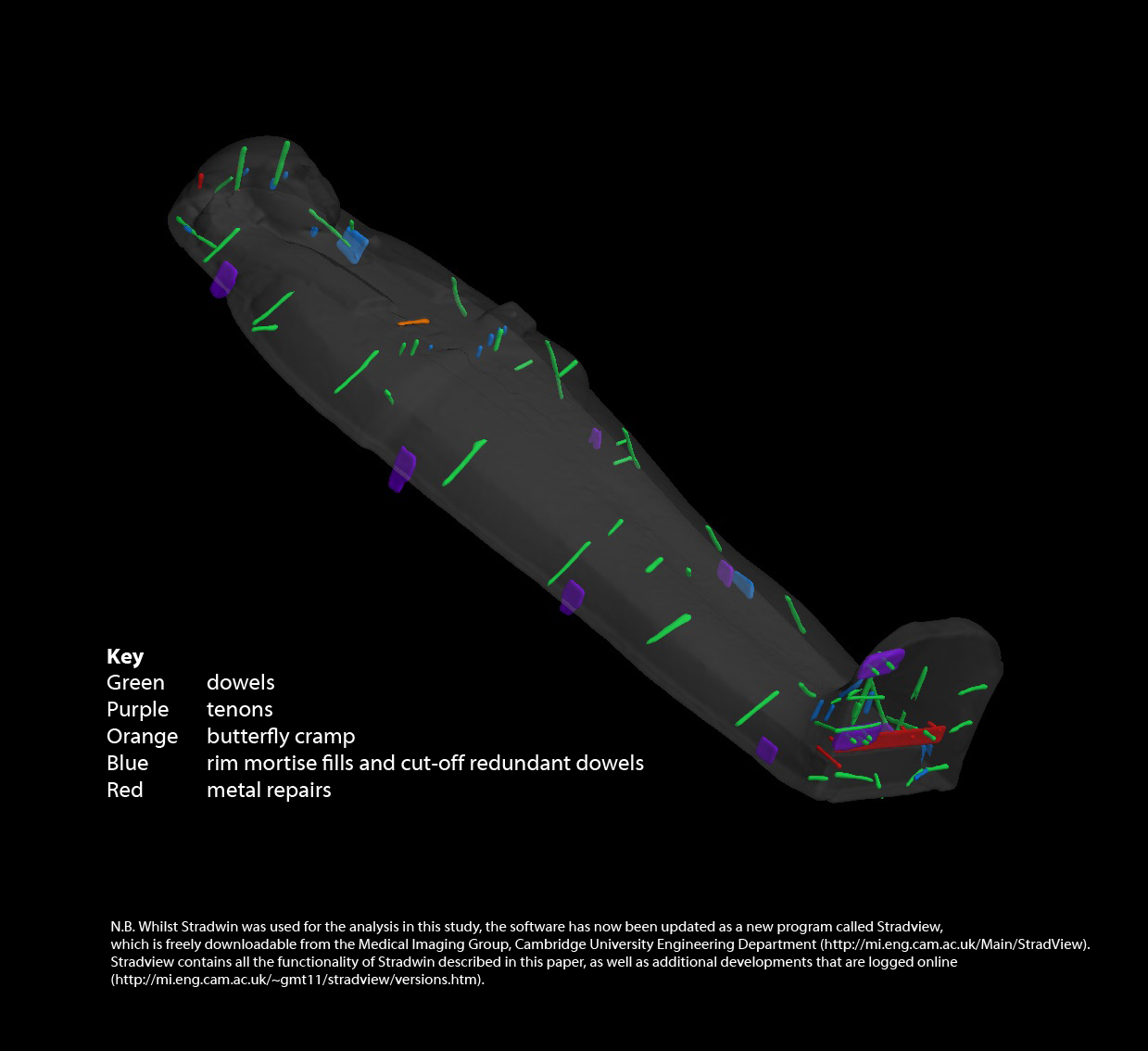

All the different connectors, ancient and modern, that hold the coffin lid together are shown here

In summary, is it possible that these are the sides of an older coffin box that originally had straighter, more upright walls that have been made into a curvier, slightly more flared shape and also that the left hand rim of the current lid and the left hand side of the current box both come from the same older coffin.

The size and structural fragility of the outer coffin have thus far precluded the possibility of undertaking CT scanning on either the box or the lid. However, the visible evidence and the images from X-radiography have revealed a number of features that suggest re-used wood. On the box these include both empty and paste-filled halves of mortises and dowel holes on the foot end boards. Also, the scarf-jointed section on the foot end of the lower plank on the proper left side ends in a dowel hole cut through the centre of its long axis. As with the inner coffin box, the exterior sides of the shoulders have been thickened with thin wood pieces glued and dowelled to the main side panels and supplemented with patches of paste to make them fit to the profile of the head end. The attachment on each side of the head end to its side panels is with three long dowels (on the proper right side these are filled with modern oak dowels, but the holes themselves appear to be ancient and to match those on the proper left side).

However, on the proper left side these partly cut across three rectangular voids. The latter have no obvious function in the current structure and their shape and position suggest that they may be mortises from the joining mechanism of an earlier object.

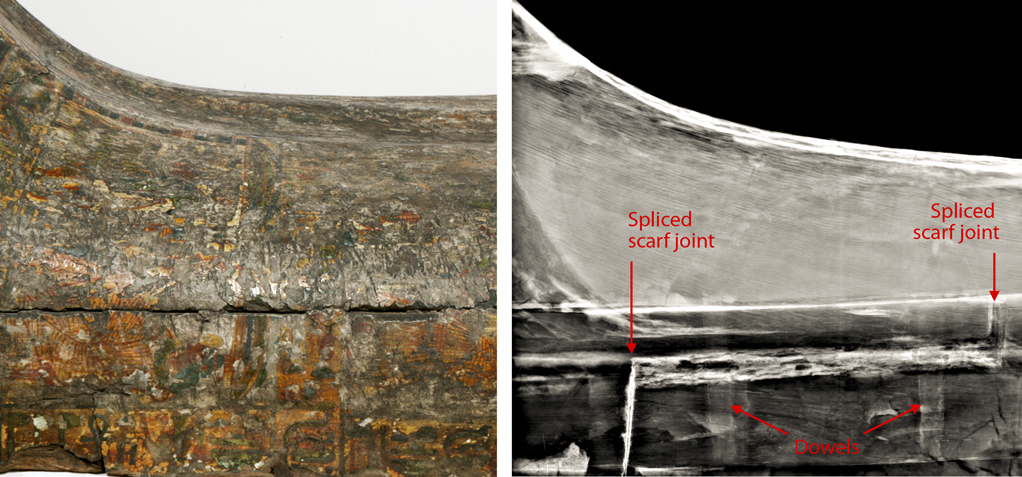

At the foot end of the lid on both sides, the rim has been lengthened by the scarf-jointed attachment of an additional piece of sycomore fig wood. In that piece on each side there is a rim mortise and tenon forming part of the current closure mechanism of the coffin. But next to each of these, there is another mortise which has been filled in with a piece of wood, dowelled through to secure it to the structure and plastered on the underside of the lid to disguise its presence, as seen on the rims of inner coffin. It seems unlikely that this is simply a positioning mistake by the carpenters, and more likely that these two added sections of the rim have come from another object and have been adapted to fit this coffin.

Cartwright, Caroline R. 2018. “Identifying ancient Egyptian coffin woods from the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge using scanning electron microscopy”. In Egyptian Coffins: Past – Present – Future, eds. Helen Strudwick and Julie Dawson. Oxford: Oxbow Books

Cooney, Kathlyn. 2017. “Coffin reuse: Ritual materialism in the context of scarcity”. In Proceedings First Vatican Coffin Conference 19–22 June 2013, eds. Alessia Amenta and Hélène Guichard, vol. 1, 101-112. Città del Vaticano: Edizioni Musei Vaticani

Strudwick, Helen. 2017. “The enigmatic owner of the coffins of Nespawershefyt at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.” In Proceedings First Vatican Coffin Conference 19-22 June 2013, eds. Alessia Amenta and Hélène Guichard, vol. 2, 521-528. Città del Vaticano: Edizioni Musei Vaticani

Dawson, J. and T. Turmezei. 2021. ‘Re-cut, re-fashioned, re-used: CT scanning and the complex inner coffin of Nespawershefyt’. In R. Sousa, A. Amenta, K.M. Cooney (eds.) Bab El-Gasus in Context: Rediscovering the Tomb of the Priests of Amun. Rome: L’erma di Bretschneider, 485–510

Dawson, J. 2018. How to make an Egyptian coffin: the construction and decoration of Nespawershefyt’s coffin set. Cambridge: Fitzwilliam Museum.

Dawson, J., T. Turmezei, G. Killen and H. Strudwick. 2022. ‘Revealing Interiors: CT scanning and microCT scanning of wooden coffins’. In B. Gehad and A. Quiles (eds.) Proceedings of the first international conference for Science of Ancient Egyptian materials and technology (SAEMT), Cairo 4-6 November 2017. Cairo: IFAO, 35–47

Nespawershefyt's inner coffin lid

Joints used in coffins in the Fitzwilliam Museum's Egyptian collection

The broken foot of Nespawershefyt's mummy board

Detail of Nespawershefyt's face depicted on the inner coffin lid

The edges of the mirror-image base boards of the outer coffin box are marked in blue on this photograph.

Marked up image of Nespawershefyt's mummy board showing its construction

Single CT image (transverse) through the inner coffin box

CT imaging revealed the loose tenon joints (with empty peg holes) within the structure, which hold the planks of the base boards together. Planks sawn by the tangential (through-and-through) method show a characteristic grain pattern (‘slash-grain’) on their surface. This is mostly hidden by the thick layer of decoration on the Nespawershefyt set, but is also revealed by the CT imaging.

Footboard of inner coffin box with CT images of transverse sections at two different points through the depth of the footboard. 5a shows the dowels that hold the current construction together. 5b shows the redundant mortise with cut-through pegged tenon. The bright white material seen on all the CT images is the paste used as a filler and as a surface layer.

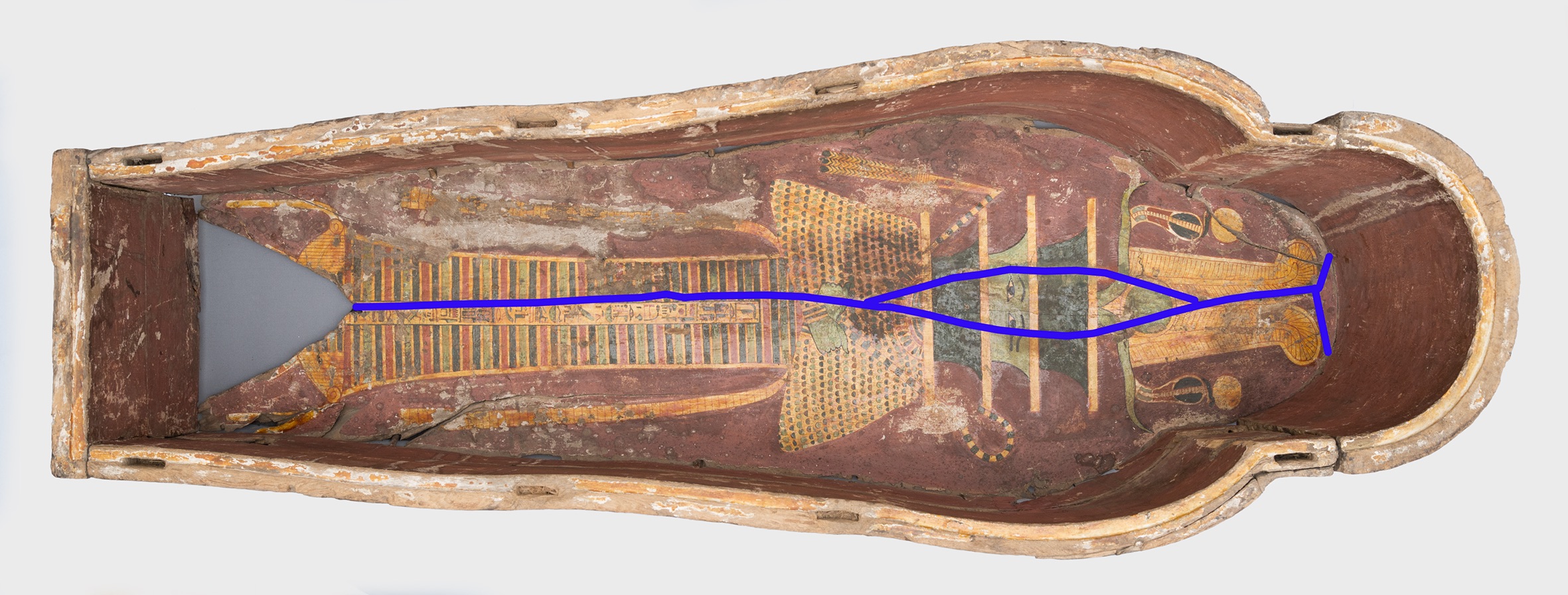

Inner coffin box. The white ovals on 7a mark the position of the strips of wood added to the interior surfaces of the side walls. The green arrows on the CT image 7b, which shows a slice from below the rim surface, mark the full length of these added strips. The strips (both of which have areas of loss) are visible also on the CT coronal slices shown in fig. 6c and fig. 10. The blue line on each side panel on 7b is drawn through the old rim mortises.

Inner coffin box. On fig. 6a and the CT image of the rim (6c), the current rim mortises are marked with blue arrows, the redundant ones with red arrows. Fig. 6b shows a CT image (sagittal section) of the proper right side panels of the box at the position of the third mortise down from the head end. In addition to the current rim mortise (empty) and the redundant rim mortise (partially filled with a piece of wood and covered at the rim surface with paste), this image shows the internal pegged tenon that joins the top and bottom side wall planks together. N.B. On this CT image and on fig. 7b and fig. 10, the elbow areas of the box are indistinct. This is because, at the rim level, the elbows fell outside the mathematical reconstruction field of view diameter of 50 cm. Separate scans were made to capture the detail here by shifting the position of the coffin box in the scanner. However, for operational reasons, this was possible only with the proper right elbow. The detail is not critical to the point illustrated here as there are no rim mortises in the elbow area.

Coopered head end of the box and attachment of this to the side panels of the box (8b). The exact positions of the coronal view slices in the blue (8a) and red (8c) rectangles are indicated by the blue and red lines acess 8d-f. So, the blue rectangle slice is close to the rim surface of the box, the red rectangle slice about a quarter of the way down the depth of the box. The turquoise line on the photograph (8b) shows the position of the transverse slice 8e. The blue arrows (8a) mark the mortise and tenon joints that hold the current coopered construction together. The red arrows mark the bigger mortises that seem to belong to a redundant structure. The pink oval on 8e shows that reshaping of the plank on the external face of the wall cut through the mortise. It was filled with a piece of wood covered over and held in place by the textile and paste decorative surface layers. The green arrows mark the dowels that join the coopered head end to the current box side panels.

Inner coffin lid showing the current rim mortises (marked by blue arrows) and the redundant rim mortises on the proper left side (marked by red arrows), together with the now detached fill piece (9d) that had been used to pack the cut-through mortise.

CT image of the lid rim placed over the box, showing how the redundant mortises (highlighted in pale yellow) on the proper left sides of both line up with each other.

These CT scanning images of the foot end of the inner coffin lid reveal the extent of re-worked and re-used wood in the coffin and show some of the compromises and patching that the carpenters had to employ.

The pegged, spliced scarf joint of the outer coffin lid is very hard to see from the outside of the object, but shows up on the X-radiograph, together with the two dowels that hold it together.

This image, generated from the CT scans, shows all the different connectors that are present in the inner coffin lid. (Image created by Tom Turmezei using Stradwin (c) The Fitzwilliam Museum and Tom Turmezei)