This page gives a glossary to terms our project uses when discussing coffin fabrication.

A rectangular coffin, with no shaping. Often with an eye panel on one side at the head end of the coffin.

A human-shaped coffin. Middle Kingdom anthropoid coffins were meant to lie on their side. Post-Middle Kingdom coffins were designed to lie on their backs.

An anthropoid coffin type from the Second Intermediate Period, introduced at Thebes, characterised by a pattern of feathers covering the exterior of the coffin (rishi is derived from the Arabic term for ‘feather’). This type of coffin seems to have developed at Thebes.

A rectangular four-poster type of outer coffin, with a vaulted lid, typical of the 25th/26th dynasty (Late Period).

25th/26th dynasty coffins usually consist of an outer qersu coffin, plus one or more anthropoid coffins inside, one of which may be a cartonnage mummy case.

An anthropoid coffin with a box that has a shaped underside, rather than a flat underside. Made in two pieces (box and lid)

An anthropoid coffin, often made of cartonnage, usually the inner coffin within a nested set of coffins. Often, but not exclusively, made in one piece.

The part of the coffin in which the body was placed. The term is used here for both rectangular box coffins and anthropoid coffins.

The part of the coffin that was placed on top of the box. In an anthropoid coffin, this would be the part that resembles the front of the head and body of the person.

The bottom (long axis) of the coffin box.

The short panel at the foot end of the coffin box and lid.

A mask is an object that lies directly over the face of a mummy. This term should not be used for a coffin face.

This term is used only for a coffin made of stone. All sarcophagi are coffins, but not all coffins are sarcophagi.

Rounded wooden cylindrical peg’. NB: ‘dowel’ is used instead of ‘peg’, but ‘peg’ can be used as a verb, e.g. ‘dowels were used to peg things together’.

Wood is a material; ‘wooden’ is an adjective. Items made of wood should be described as ‘wooden’ or ‘(made) of wood’, e.g. ‘a wooden statue’, ‘a panel of wood’.

Material used to stick things together, e.g. glue, gum

Material holding paint together, often called ‘medium’.

Paint is made up of pigment plus a binder.

In Egypt, usually a resin intended to give a glossy sheen to a surface.

‘Infill’ used for pieces of wood or other material used to fill large gaps in construction.

A ‘fill’ will usually be of paste and may be part of a preparation layer.

A piece of decoration made completely separately and usually inset within a retaining framework.

Also known as through-and-through or slash sawing. The trunk or log is sawn down its long axis. Timber cut this way can be recognised by the slash-grain pattern on the planks. It is the most economical way to cut up timber, but the planks are prone to ‘cup’ because the wood dries and shrinks unevenly across the width of the plank.

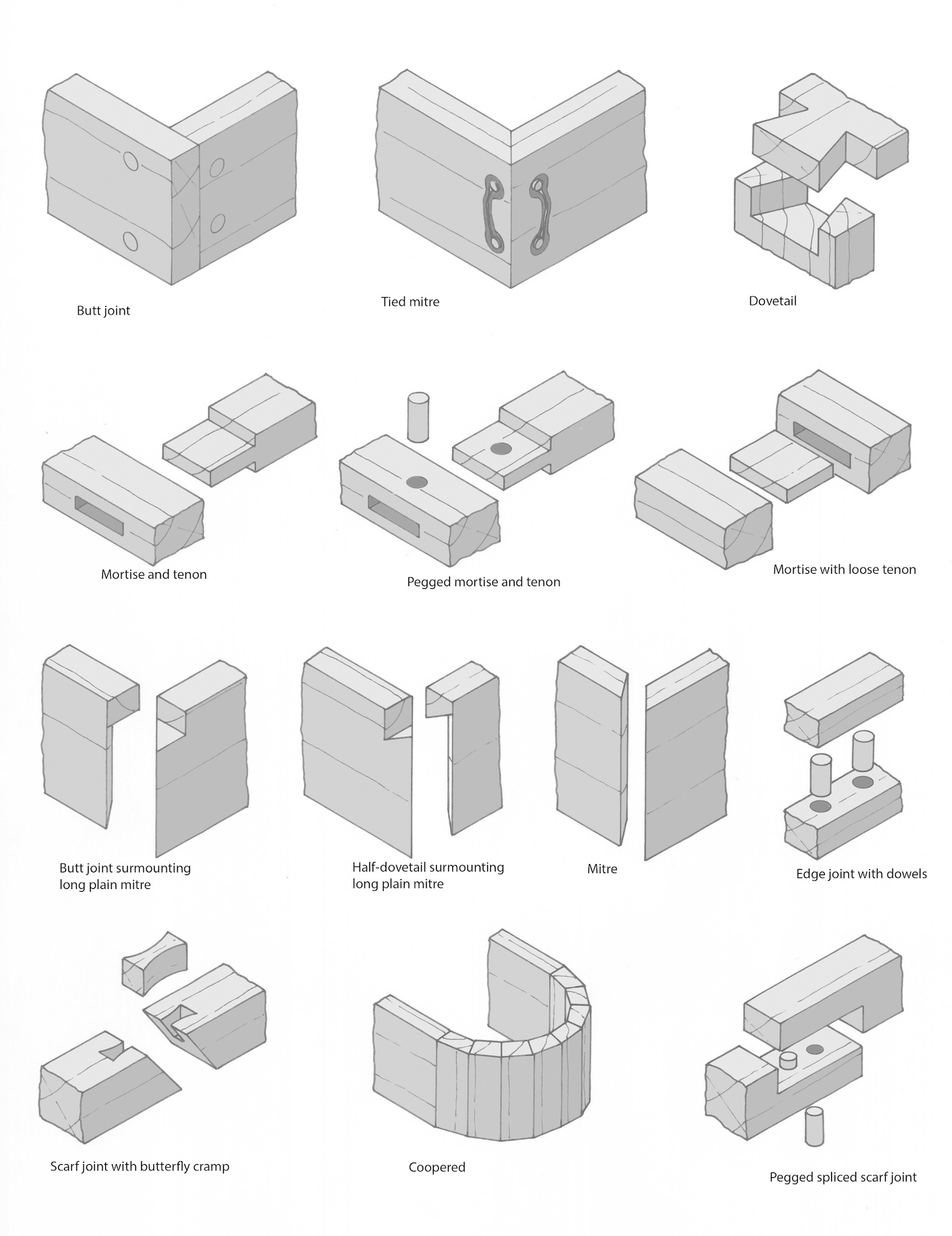

The Fitzwilliam’s Egyptian coffins contain examples of the following wood working joints:The Fitzwilliam’s Egyptian coffins contain examples of the following wood working joints:

{width=300}

{width=300}

A laminated material constructed of layers of linen or papyrus soaked in glue, with a layer of paste on the internal and on the external surface.

A writing material made from the inner pith of papyrus plant (Cyperus papyrus) stems. The term papyrus (plural: papyri) is used also to describe documents made from this material.

A term that has been used to describe a range of glazed composition materials, but is usually defined as a shaped core made of crushed quartz or sand mixed with small quantities of lime and natron or plant ash, coated with a glaze and fired in a kiln. The glazes usually contain copper, which gives the faience a blue-green colour.

A name commonly applied to Egyptian glassy materials. Frit has the same composition and structure all the way through the material (as opposed to the distinct core and glaze layer of faience). The pigment Egyptian blue is a frit. If it was ground up, mixed to a paste with water, then shaped and refired, an object made of blue frit (e.g., an amulet) could be produced.

In describing Egyptian objects, the term ‘plaster’ is often used rather loosely to cover both true plasters (made from lime or gypsum cements) and pastes made from a binder (such as animal glue) mixed with calcium sulphate (often called gesso) or with calcium carbonate (often called whiting). To avoid confusion and to address the fact that sometimes mixtures of all these materials can be present, together with clay minerals and vegetable fibres, the term ‘paste is used in our research project as it implies no particular chemistry or technology.

A layer of paste applied across the coffin to provide a smooth, neutral surface to which paint can be applied. Sometimes known as a ‘ground’ layer.

When it has not been possible to characterise pigments fully, their elemental make up has been recorded as, for example, ‘calcium-based’ or ‘copper-based’.

Egyptian blue and Egyptian green Manufactured pigments, prepared by firing copper minerals or metal with a calcium compound (like powdered limestone), silica and soda at high temperature. The principal colour component in Egyptian blue is calcium copper tetrasilicate (CaCuSi4O10), and in Egyptian green is cupro-wollastonite (CaSiO3 with copper in the structure).

Malachite (Cu2CO3(OH)2) A mineral pigment, giving a pale green colour.

Chrysocolla (Cu2H2Si2O5(OH)4) A mineral pigment with a turquoise blue colour.

Copper-wax, copper-proteinate, copper carbohydrate Green pigments produced from the reaction of copper salts with various organic media.

Verdigris (copper acetate) A copper salt that can be manufactured or found as a corrosion product. Produces a bright green colour.

Earths This is an umbrella term used to describe a range of pigments derived from naturally occurring deposits containing clay minerals, iron oxides and manganese oxides. They can be found in a range of shades depending on the purity and specific chemical structure of the natural sources, and can include red, yellow, orange and green pigments. The term ‘earth’ may be confused with ochre, which is a member of the earth pigments group, consisting of earths rich in iron oxide and iron hydroxide. Earths on ancient Egyptian objects may contain one or more of the following:

Yellow earths The iron sulphates jarosite/natrojarosite (KFe3(OH)6(SO4)2/ NaFe3(SO4)2(OH)6), and the iron oxides goethite (α-FeO·OH) and limonite (FeO(OH)·nH2O).

Red earths The iron oxides haematite (Fe2O3) and ilmenite (FeTiO3).

Green earths Celadonite and glauconite (iron magnesium silicates belonging to the mica group).

As these pigments arise from naturally occurring deposits, they often occur as a mixture and are not always easily classifiable. Where it has been possible to further identify particular pigments, this is normally indicated in the text.

Calcite (CaCO3) Calcium carbonate.

Micritic calcite Microscopy term to describe calcite visible as very fine particles, usually originating from chalk.

Sparitic calcite Microscopy term to describe calcite that forms into crystals, usually suggesting limestone origin.

Huntite (Mg3Ca(CO3)4) Magnesium calcium carbonate, a bright white pigment.

Gypsum (CaSO4· 2H2O) Calcium sulphate.

Bassanite (CaSO4· ½H2O) Made from roasting gypsum at high temperatures, sometimes found naturally. The modern equivalent is plaster of Paris.

Anhydrite (CaSO4) Completely dehydrated version of gypsum sometimes found naturally, or produced by heating above 200°C (392°F).

Lead white (PbCO3Pb(OH)2) Lead carbonate, an opaque white pigment.

Red lead (Pb3O4) Lead tetroxide, a bright orange-red pigment.

Cinnabar (HgS) Mercury sulphide, a vivid red mineral pigment.

Orpiment (As2S3) Arsenic sulphide, a lemon yellow pigment.

Realgar/pararealgar (As4S4) Arsenic sulphide (but different crystal structures), orange pigments. Pararealgar is a degradation product of realgar.

Carbon-based black A group of pigments made mainly of carbon. In Egypt, these are principally soot and charcoal.

Lake pigments Also known as dyestuffs, these are organic pigments that can be made from certain insect or plant matter. The colour is extracted and precipitated onto a metallic salt substrate. Lake pigments found on Egyptian objects include:

Madder Pink dyestuff made from the root of the madder plant Rubia tinctorum fixed on a mineral base such as aluminium sulphate.

Indigo Blue dyestuff from plants of the Indigofera species fixed on a mineral base.

All the techniques described here are based on examining the interaction of the materials of the object with radiation from various parts of the electromagnetic spectrum and recording the results.

The following techniques can be carried out directly on the object:

In contrast, the following techniques require a small sample to be removed from the object:

Visible-light induced luminescence (VIL) photography Egyptian blue pigment emits particular bands of infrared radiation when lit with visible light. VIL photography captures this emission using a sensitive camera filtered to let only those bands of infrared light through. All the Egyptian blue (even minute particles) shows up as bright white on the photograph, enabling identification of lost areas of decoration or traces of inscription.

Ultraviolet (UV) fluorescence When subjected to ultraviolet radiation, some materials emit (fluoresce) visible light in characteristic colours. For example, under UV light, pistacia resin varnish fluoresces greenish-yellow and the pink pigment madder fluoresces bright orange. This technique clarifies where these materials are located on the object (fig. XX) and also shows up areas of restoration, which are often made of materials that do not fluoresce (fig. XX).

Infrared (IR) reflectography Infrared radiation is absorbed by certain painting and drawing materials, especially carbon-based black pigments. This type of radiation can penetrate through paint layers and can be captured photographically with a camera sensitive to infrared radiation. Underdrawings executed in carbon-based black show up as black on the image, even when not visible on the surface. It is possible, therefore, to see where they have been used in early drawing stages of the decoration (see cat. 22, fig. XX [IR photo. In the caption explain that the black areas are carbon black pigments]).

UV-VIS-NIR fibre optic reflectance spectroscopy (FORS) This method measures colour: the paint is illuminated with radiation from the ultraviolet, visible, and near-infrared regions of the electromagnetic spectrum. The light reflected off the surface is captured and the spectrum recorded by a computer. Many pigments produce spectra with key features that are specific to them, allowing the material to be identified through comparison with reference spectra (fig. XX).

X-Ray fluorescence spectrometry (XRF) A small area of the object is bombarded with X-rays. These X-rays excite atoms within the material, causing them to emit secondary X-rays. The energies of these secondary X-rays (fluorescence) are characteristic of the elements present, such as iron or calcium. This is a quick, sensitive method for identifying inorganic pigments containing heavy elements (e.g., orpiment, which contains arsenic).

X-radiography X-ray radiation penetrates through matter: the denser a material is, the more difficult it is for the X-rays to penetrate. A sheet of film is placed under the object and records the relative intensity of the X-rays that emerge after they have passed through the object. An X-radiograph shows the internal structure of the object and clarifies the assembly of a coffin. (fig. XX).

Computed tomography (CT) imaging Conventional X-radiography provides a two-dimensional image of the interior of the object. CT, sometimes known as CAT scanning, is similar to standard X-radiography, but in this technique the data is collected simultaneously in different planes, producing cross-section slices (like the slices in a loaf of bread). Each slice can be examined individually and three-dimensional images of the object can be produced, providing a wealth of detail about internal structure (see cat. 27 [E.1.1822], fig. XX; cat. 55 [E.63.1903], fig. XX).

Polarised Light Microscopy (PLM) A tiny sample of pigment, taken from the coffin surface, is mounted in adhesive on a microscope slide. Light is passed through the particles, which are viewed down the optical microscope to record features such as size and shape. The use of polarising filters causes the particles to interact with light in different states. All these features can be diagnostic of specific pigments (fig. XX).

Cross-section analysis A minute fragment from the painted surface is embedded in resin, ground and polished. This cross section is viewed in reflected light under an optical microscope. It can reveal information about the materials and techniques used by the artist and show up later restorations (fig. XX).

Scanning electron microscopy–energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM/EDX) A powerful microscope irradiates a sample with a beam of electrons. These particles scatter on the surface and produce a high-magnification image of the sample. The electron beam also causes X-rays to be generated by the elements in the sample. When used on a cross section, this technique can show where inorganic pigments with heavy elements are located within a layer structure.

X-Ray powder diffraction (XRD) When a tiny powdered sample of paint is bombarded with X-rays, the shape of the crystal structure causes the X-rays to change direction and intensity in distinctive patterns. These patterns can help identify pigments and pastes, and can differentiate between materials with similar chemical compositions but different structures (e.g., orpiment and realgar, both made of arsenic and sulphur but with different structures).

Raman spectroscopy A tiny sample is subjected to a laser beam (wavelengths in the UV, visible or near-infrared parts of the electromagnetic spectrum). The resulting vibration of chemical bonds in the molecules gives information about their structure. It can identify materials and differentiate between certain molecules with similar chemical compositions but different structures.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) Molecules in a sample all absorb infrared radiation at specific wavelengths. By measuring the energy absorbed by the movement of the bonds in the molecules, it is possible to identify the class of organic material present (e.g., a plant gum as opposed to a tree resin or animal glue). FTIR can distinguish between organic materials found in the binding media or varnish and identify certain pigments (such as calcite, indigo and lead white) which absorb energy in the infrared.

Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) Gas chromatography separates out the individual molecules in a complex mixture. Then each of the individual molecular components is identified by mass spectrometry. The technique distinguishes between different species of organic material in the paint binding media or varnish layers: for example, determining whether a natural resin varnish is a pistacia or conifer resin.

Wood identification Tiny samples of ancient Egyptian wood are sectioned to reveal details of the cellular wood anatomy needed for scientific identifications. Transverse, radial longitudinal and tangential longitudinal sections are then examined under high magnifications using the optical microscope in reflected light mode as well as the variable pressure scanning electron microscope (fig. XX). Reference specimens and wood anatomy databases are used for comparison.