Object number: E.2.1888

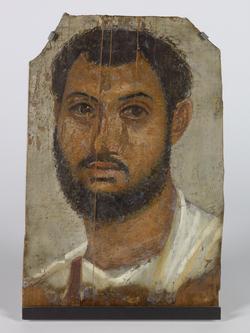

Description: Mummy portrait of a bearded man from Hawara, mid-late 2nd Century AD.

Measurements: H. 32.5cm W. 22.5cm D. 0.2cm

Analysis: Encaustic on wood. The support is a single piece of lime with vertical grain of only two rings’ thickness. The wood was identified by Caroline Cartwright of the British Museum in 1996. The painting has split into two separate pieces between the proper right eye and the nose. A piece of tape has been applied to the reverse of the split but there is a gap of over 1mm between the two pieces. In addition, there are several other major splits and bulges (see the accompanying photograph), some of these appear to be exacerbated by the auxiliary support. The sides and upper corners appear to have been trimmed down after painting. There are areas of dark resin and textiles adhered to the reverse of the panel. These are visible in X-ray and are materials associated with burial.

As is the case with E.102.1911, the panel has been glued to an auxiliary plywood support. This treatment is unrecorded but must have occurred after the photograph was taken by Budde in the 1950s, at which point the painting was pinned to a different board but apparently not glued. As far as it is possible to tell, the panel has only been glued to the plywood at certain points around the edges. The glue is now yellow and brittle. It is water soluble and is delaminating from the painting in several places.

There is a greyish white underlayer, certainly beneath the white clothing and the background. However there is no overall ground layer. This greyish white underlayer has much the same appearance as the rest of the paint and is almost certainly wax-based. There is no ground or paint present on the lower part of the panel. The painting was therefore certainly never full-length. The way that the paint ends loosely and roughly indicates that the bottom portion was always intended to be covered by the funerary wrappings. No underdrawing is visible.

The paint medium is encaustic – either pure beeswax or a saponified beeswax (Punic wax). Given the presence of lead soaps in the samples tested, it is impossible to say whether the medium was deliberately saponified. The use of esparto wax has been discounted. The pigments identified from sampling include; chalk/calcite, lead white, dolomite, gypsum, bone white, quartz/glass, alumina, charcoal, yellow ochre, red lead, red lake (type unidentified) and iron oxide red. It is possible to discern both the use of brushes and of tools on the painted surface. The painting style is bold and loose and the painting has the appearance of having been executed rapidly to a well-practised formula. A layer of wax applied by Petrie has caused a darkening of the painting as a whole. It is possible to see that the overall appearance was significantly lighter from the edges where Petrie did not apply the wax coating. There is a large area of loss to the proper left of the nose. This has been quite crudely retouched with an earth pigment. There are other scattered losses throughout the paint film.

There are several places where Petrie’s application of paraffin wax has displaced loose flakes and re-adhered them in the wrong location (see the accompanying photograph). At present, there is an area of tenting along the line of the vertical buckle 1.5cm to the proper left of the complete split. The restraint of the plywood backing is causing this ridge to form, and the paint to crack and tent. It is possible to see from the areas around the edge where the additional layer of wax has not been applied that this layer has caused the painted surface to darken considerably. In addition, the flecks of white which disfigure much of the surface of the painting are areas of the wax layer applied by Petrie which are not adhered to the surface below. There is a mark of blue paint from past framing/display in the top proper left hand side.

The portrait has a coating of paraffin wax which was applied by Petrie fairly immediately after excavation. Petrie describes two techniques for the wax consolidation of these paintings in Roman Portraits and Memphis (IV) in 1911. In some cases it is sometimes impossible to tilt the panel without the paint falling off. There is no preservative so satisfactory as flooding over with melted paraffin wax; this must be hot enough to penetrate the cracks freely, but not so hot as to melt up the ancient wax paint. All surplus can be removed by scraping down and gentle melting. If the flakes of paint become shifted out of place, the waxed face can be slowly melted by hanging a hot iron just clear of it, and then the paint can be pressed down in position by a wet finger, and the surplus paraffin squeezed out…Where the changes have been less, and the colour is only brittle and liable to slight crumbling, then a thin coat of paraffin has been added, by spreading over the face and rubbing into the cracks a soft butter of paraffin and benzine, about half and half. As the benzine evaporates, the paraffin can be gently melted into the cracks, and any surplus removed. Which of these two techniques has been used in this case is unclear. In addition there are occasional accretions of resinous material from the burial, obviously beneath the wax layer. The wax layer is dull in appearance and seems to have imbibed a considerable quantity of surface dirt.

Commentary: In 1888 Petrie discovered the painted portraits at Hawara in the Fayûm. In all, Petrie removed 146 from the ground in two seasons of excavation (1888 and 1910/11). This panel comes from the first season of excavation. It was given to the Fitzwilliam Museum by Petrie in 1888.

Other relevant objects in the Museum’s collection: E.63.1903, E.5.1981, E.102.1911, E.111.1932, E.W.50, E.W.48, E.110.1891, E.W.52.

Mummy portrait of a bearded man from Hawara. Fitzwilliam Museum: E.2.1888.