Early Burials

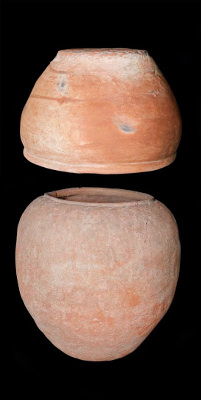

From about 4400–3200 BC burials took the form of simple pits in the sandy desert, at the edge of the Nile floodplain. The dead were laid on their sides in a contracted, foetal position, sometimes wrapped in reed mats or animal skins. Pottery bowls and beakers were included, probably to ensure the dead had food and drink with them, together with cosmetic palettes for grinding eye paint.

After a time, the Egyptians began to make special containers the bodies of the dead, including included reed baskets, wooden coffins, pots or simple depressions in the sand or rock, which were lined with bricks and then plastered. Bodies were usually placed in a contracted foetal position, lying on their sides. Evidence from recent discoveries shows that this position continued to be used in ancient Egyptian burials of all periods, although at later dates it was restricted to people who could not afford an elaborate burial.

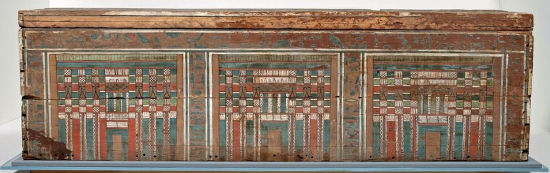

Box Coffins

During the Old Kingdom (about 2700–2170 BC), the period when the pyramids at Giza were constructed, there was a change in the way bodies were laid out for burial: instead of being in a crouched position, the dead were laid out with straight legs. Their arms were sometimes crossed over the chest. There were also some early attempts at mummification, particularly by removing the internal organs and preserving them separately. These innovations began with members of the royal family but soon spread more widely.

The new position of the dead in their burials led to the development of rectangular coffins, made of wood or stone. These are often called box coffins and they continued to be used for most of the Middle Kingdom (about 1020-1790 BC).

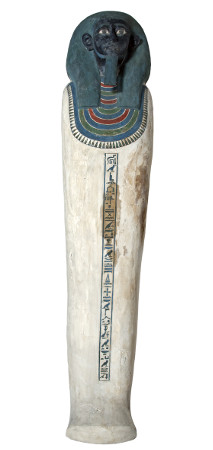

Early Anthropoid Coffins

During the Old Kingdom (about 2700–2170 BC) the Egyptians began to build up the facial features of the dead in paste over the mummy wrappings. By the Middle Kingdom (about 2010–1790 BC), however, a new feature appeared in the form of a separately-made mask, often of cartonnage or wood with a cartonnage overlay. This covered the face and sometimes the whole head and shoulders of the body, and was painted with a stylised image of the features of the deceased. At the same time, the quantity of linen used in wrapping the dead increased.

The combination of white linen and a mask came to be used by the Egyptians as a way of indicating that the dead were prepared for entry into the afterlife. They called this form sah. As a result, the coffins themselves began to be shaped like a mummified figure wearing a mask. These early anthropoid (human shaped) coffins were placed inside an outer rectangular coffin, where they lay on their sides with the head of the anthropoid coffin facing the eye panel on the outer coffin.

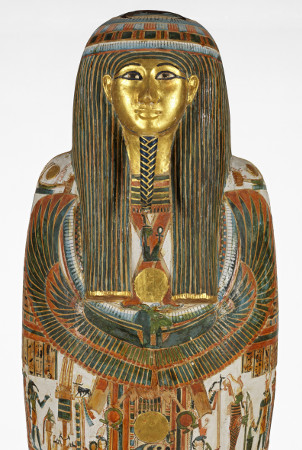

Decorated Anthropoid Coffins

During the Twentieth Dynasty (about 1185–1070 BC), the temple of Amun-Re at Karnak (just north of present-day Luxor) became increasingly powerful. Eventually, its high priests proclaimed themselves kings, at least in the area around Luxor. In the Twenty-first Dynasty (about 1070–945 BC), temple officials like Nespawershefyt (whose coffins are displayed in the centre of the room) placed great stress on the status that came from working there. They were keen to maintain this in the afterlife, so their job titles were frequently repeated in the inscriptions on their lavishly decorated coffins.

In the Twenty-second Dynasty (about 945–735 BC), for unclear reasons, it seems that there was a change in the burial equipment used by officials and priests from this temple. They were buried in cartonnage inner coffins, rather than wooden ones, and their outer coffins were very plain indeed. It is possible that cartonnage was used for the innermost coffin because this stiff and fragile moulded material could not be recycled as easily as wood. It is noticeable that the burial of Nakhtefmut (shown in the wall case) includes a set of cheaply made shabti figures in a crude wooden box. While the inscriptions on Nakhtefmut’s coffin mention his job titles, these are not repeated. Perhaps a close relationship with Karnak was less important at this time and, instead, Nakhtefmut’s main focus is on listing his ancestors.

Nested Coffins

During the Twentieth Dynasty (about 1185–1070 BC), the temple of Amun-Re at Karnak (just north of present-day Luxor) became increasingly powerful. Eventually, its high priests proclaimed themselves kings, at least in the area around Luxor. In the Twenty-first Dynasty (about 1070–945 BC), temple officials like Nespawershefyt (whose coffins are displayed in the centre of the room) placed great stress on the status that came from working there. They were keen to maintain this in the afterlife, so their job titles were frequently repeated in the inscriptions on their lavishly decorated coffins.

Inside the coffins, pieces of cartonnage were laid over, or sewn on to, the wrappings surrounding the mummified body. These usually included at least a funerary mask and a winged figure of the goddess Nut, with her arms spread out over the chest of the deceased.

Egypt Under Foreign Rule

From 525 BC, Egypt came increasingly under the control of foreigners. In 332 BC it was conquered by Alexander the Great and there followed a period of Greek rule, known (from 305 BC) as the Ptolemaic Period, which ended with the reign of Cleopatra VII. In 30 BC Egypt became part of the Roman Empire.

For most of this time, Egyptian burial customs remained relatively unchanged and images of gods such as Isis, Osiris and Anubis still appeared. Many coffins survive that are recognizably Egyptian. There are anthropoid and qersu coffins (with four corner posts) but, inside these, the dead were wrapped in decorated linen shrouds rather than laid in inner coffins.

There were also some significant changes in decoration. The focus was no longer on inscriptions giving a person’s name and job titles; instead it became important to create more individualized images of the dead, including plaster masks or portraits, painted on the shrouds or on wooden panels. New materials, including pigments such as red lead and lead white were introduced. The plant-based deep blue indigo and bright pink madder had long been used as dyestuff in Egypt, but now the colour was extracted and fixed onto a ground mineral base, making additional vivid paints for the palette.

Re-used wood

Many of the coffins displayed in this exhibition incorporate pieces of re-used wood. These may have come from coffins that were recycled or from older coffins that were reworked into new ones. From the late New Kingdom (about 1170 BC) onwards, there is clear evidence that complete coffins from older burials were being re-modelled and repainted for use in new burials.

We cannot be certain what happened to the earlier burials from which these coffins originated. We do know from contemporary official records that tomb robbery seems to have been rife at the end of the New Kingdom and continued into the Third Intermediate Period (about 1070–715 BC). Since wood was an expensive material, it is likely that coffins would have been valuable items to steal and sell on.

Early burial: Pot burial made from Nile silt, provenance unknown. Fitzwilliam Museum collection: E.P.550 and E.P.549.

Box coffins: Middle Kingdom box coffin belonging to Nakht from Beni Hasan. Fitzwilliam Museum collection: E.68.1903.

Cartonnage: Cartonnage face mask of Tjay from Beni Hasan. Fitzwilliam Museum collection: E.68.1903.

Early anthropoid coffin: Belonging to a man named Userhet from Beni Hasan. Fitzwilliam Museum collection: E.88.1903.

Decorated anthropoid coffin: Cartonnage coffin of Nakhtefmut. Fitzwilliam Museum collection: E.64.1896.

Nested coffins: Late Period coffin set of Pakepu. Fitzwilliam Museum collection: E.2.1869.

Egypt under foreign rule: Gypsum plaster mask from a Roman coffin. Fitzwilliam Museum collection: E.3.1906.

Egypt under foreign rule: Cartonnage footcase. Fitzwilliam Museum collection: E.103b.1911.

Re-used wood: Box coffin of Nakht from Beni Hasan. Fitzwilliam Museum collection: E.68.1903.

Re-used wood: Detail of the inner coffin of Nespawershefyt. Fitzwilliam Museum collection: E.1.1822.