By Flavia Ravaioli, Conservator

In 2016 the Fitzwilliam Museum made the headlines with a remarkable discovery: a miniature Egyptian coffin that had been thought to hold mummified organs was found to contain an embalmed human foetus, the youngest ever known to be buried in Ancient Egypt. The coffin had been X-rayed in preparation for the ‘Death on the Nile’ exhibition, but when the results appeared inconclusive it was decided to CT-scan its contents. This revealed a mummified foetus only 18 weeks into gestation, its arms ritually folded over its chest. It was wrapped in bandage, over which molten back resin had been poured before the coffin was closed.

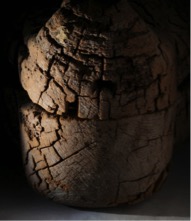

The coffin that holds the bundle is of interest in itself. Excavated in Giza by the British School of Archaeology in 1907, it came to the Museum in the same year. Though the wood is poorly preserved, and the painted surface entirely lost, surviving details of the face and ears show that it was skilfully carved. Measuring only 43 cm in length, it is a fine example of an anthropoid coffin of the Late Period (664-525 BC), built on a tiny scale.

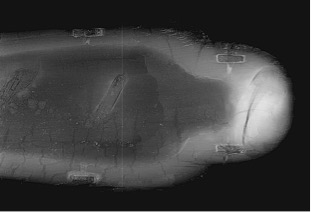

I recently re-examined the artefact with the aim of completing its technical study and assessing the condition of the vulnerable surface. X-ray examination confirmed that the box and lid are each carved out of a single piece of cedar wood, joined by four pegged tenons on each side. The deterioration of the wood is so severe that deep crevices are visible in X-rays of the box.

A powdery white material can be seen on the ears, face, chest and feet, particularly in recessed areas. This shows that the surface would have been covered in a white preparation layer (typically calcite mixed with animal glue), applied over the wood to create a smooth surface for painting. Traces of black resin are also visible, which may be unintentional “splashes” from when the burial bundle was coated.

Although to the naked eye the surface appears colourless, microscopic examination reveals the occasional loose pigment particle. The main colour visible is blue, seen on the wig and the collar; this is likely to be Egyptian blue, a glassy, copper-based frit commonly used in the ancient world, and one of the earliest synthetic pigments. Red, yellow and green pigment particles are also visible under the microscope, but it is hard to be sure that these are original.

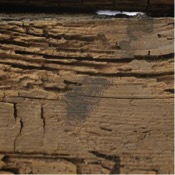

Close examination also reveals signs left by craftsmen at the time of manufacture: a fingerprint in black, likely left at the time the coffin was closed after the molten resin was applied within; chisel marks on the wooden surface around the head, which might have served to roughen the surface before the preparation layer was applied.

The surface was investigated further with VIL (Visible Light Induced Luminescence), used to detect the pigment Egyptian blue, and UV (ultraviolet) light, which helps reveal the presence of varnishes and resins, but no further traces of the original decoration could be seen. The fibrous structure of the wood is severely weakened by brown-rot, a type of fungal degradation, also responsible for the pronounced fracturing of the surface (known as “cubing”). Entire sections of the surface are lost, particularly on the sides, while the head is better preserved. The superficial layer easily crushes and powders on touch – a symptom of compromised cellular structure, where cell walls are degraded due to cellulose depletion.

The conservation treatment aimed to reinforce particularly degraded areas of the surface to avoid further losses. After cleaning with a soft brush, smaller wood fragments were consolidated with a cellulose-based adhesive (Klucel G 2% w/v in 50:50 IMS and deionised water). Larger fragments were secured in place by inserting Japanese tissue tabs soaked with a starch paste (10% w/v sodium alginate and arrowroot). The powdery plaster and pigment residues had to be consolidated without touching the surface, as any contact with a brush would have picked up the loose particles. This was achieved by applying a consolidant as a mist using a nebulizer (Funori 1.5%).

Miniature coffin with contents.

Detail of the head end of the miniature coffin.

X-ray image of the coffin showing deep crevices which is indicative of deterioration to the wood.

Detail of the coffin showing traces of powdery white material and Egyptian blue pigment.

Remains of a black fingerprint left by one of the craftsmen.

Advanced imaging techniques help to detect the presence of coloured pigments, varnishes and resins.

Conservator, Flavia Ravaioli, microscopically examining the miniature coffin.